Printed Matters

500 Capp Street: David Ireland’s House

July 28, 2015From artists' monographs to beach reads, "Printed Matters" offers a monthly take by a rotating group of contributors on visual art through the printed word.

On the corner of Capp and 20th Streets in San Francisco’s Mission District stands a white house. Built in 1886, it possesses plenty of Victorian charm but lacks the ornate carpentry and color of many other historic houses, including some of its neighbors. The building, located at 500 Capp Street, is an unassuming work of art by the late Bay Area artist David Ireland and the site of a future museum dedicated to itself, founded by local arts patron Carlie Wilmans. With the house slated to open to the public in January 2016, Constance M. Lewallen’s new book 500 Capp Street: David Ireland’s House (University of California Press, 2015) is both a teaser and a primer on the house and its fascinating history.

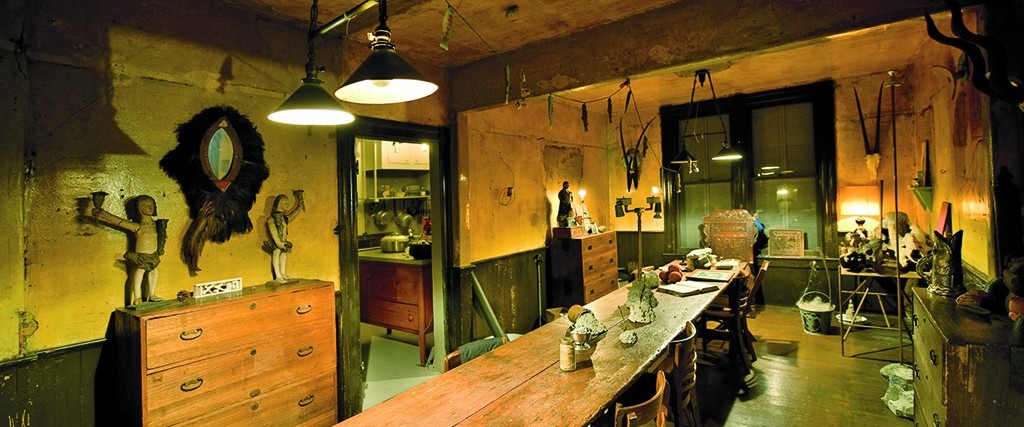

500 Capp Street, view of the dining room, 2007. Courtesy of UC Press.

500 Capp Street, view of the dining room, 2007. Courtesy of UC Press.

Many photos from the four decades Ireland lived at the house create an impression of the structure’s ever-changing nature, as well as a persistent feeling of arrested decay. Ireland regularly added to and changed the work installed in the house, but photos from as recently as 2007 show the building with its faded paint, cracked walls, and blemished wood flooring thoughtfully preserved as if it had always been a museum. It is ghostly and somewhat melancholic. During his initial renovation, Ireland removed carpeting and layers of wallpaper, restoring the house to one of its earlier states. He even stripped the paint that was under the wallpaper, revealing cracks in the plaster, which he preserved with copious coats of varnish.

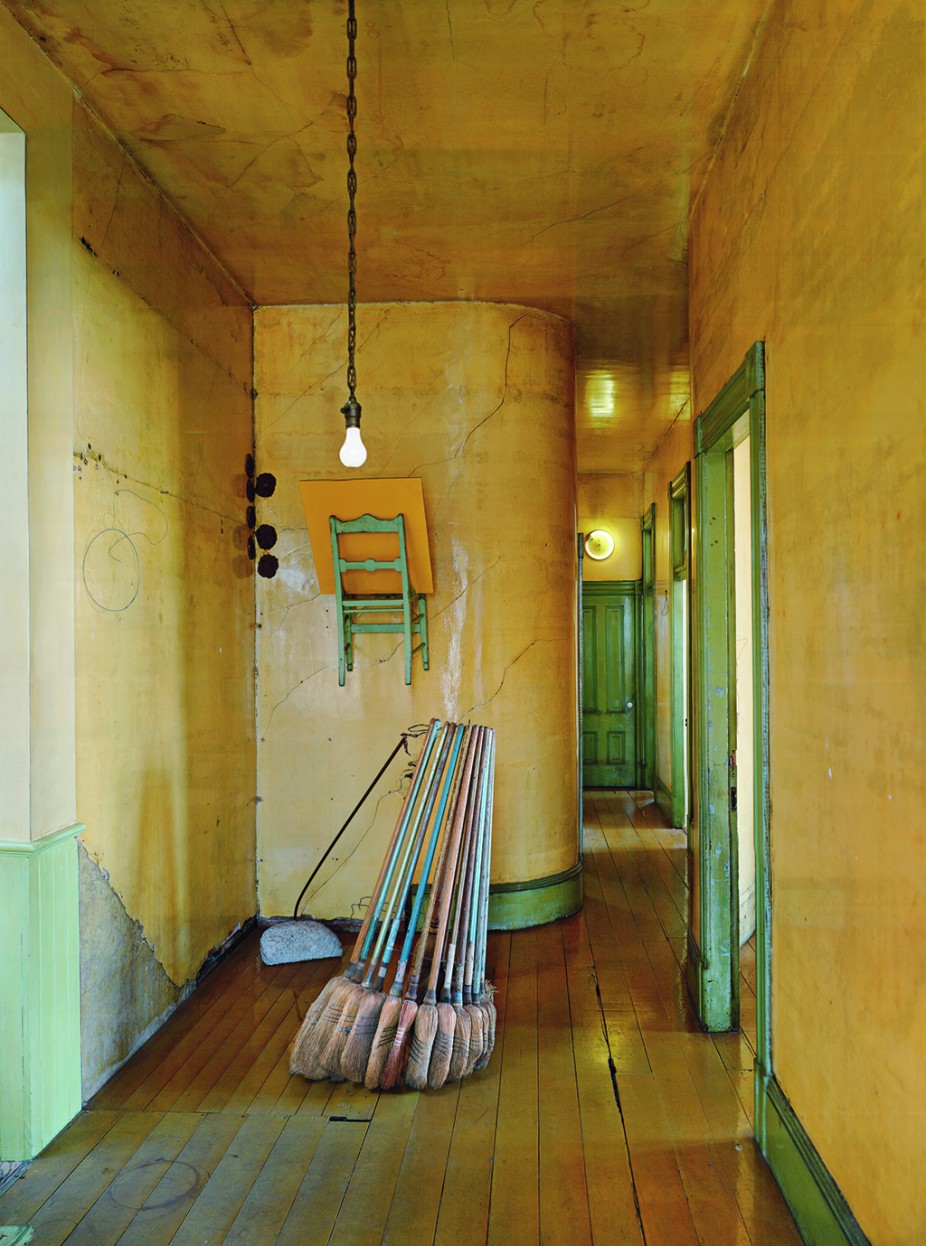

As Lewallen details, the site’s past provided considerable inspiration and material for Ireland’s work. Greub was a bit of a hoarder, and his move out of 500 Capp Street seems to have been incomplete; Ireland often likened himself to an anthropologist as he continually discovered new features and objects left over from the accordion maker’s 38-year occupation. The iconic sculpture Broom Collection with Boom (1978–88) is made from 18 used brooms that he found throughout the house. The aged brooms, arranged in a circle that seems to replicate and crystallize the passage of time, look harmonious against the house’s antique yellow walls. This eerie entity seems far more at home at 500 Capp Street than in the pristine confines of a white-cube gallery.

The first known photograph of 500 Capp Street (1886) hanging in the entry hall, 2007. Courtesy of UC Press.

The first known photograph of 500 Capp Street (1886) hanging in the entry hall, 2007. Courtesy of UC Press.

With a conceptual artist’s sense of humor, Ireland designated mundane details as works of art. While he was trying to move a heavy safe and a punch press left behind by Greub, the walls suffered several gashes and scratches. Under these blemishes, he mounted museum-like bronze plaques reading “The Safe Gets Away for the First Time November 5, 1975,” “The Safe Gets Away for the Second Time November 5, 1975,” and “The Punch Press Is Dragged Away November 5, 1975.” Lewallen’s exploration of these actions elucidates not only how Ireland saw the house and its quirks as artistic material, but also how he approached the larger world around him. She cites specific examples related to the house to explore how artists such as Joseph Beuys and John Cage influenced Ireland’s practice, and to better understand his relationship with contemporaries such as Tom Marioni and Tony Labat.

The ostensible subject of the book is 500 Capp Street, but the house actually serves as a case study, a microcosm, of Ireland and his larger career. Anyone interested in his art will find this slim publication of great interest, as the history of the house is necessarily a biography of its most notable inhabitant, landlord, and handyman. Lewallen ends her essay with the thoughtful observation that 500 Capp Street is a self-portrait of sorts, and an aptly conceptual one.

Like what you've read? Let's keep it going: Donate to our Writers Fund.