Printed Matters

Someday Is Now: The Art of Corita Kent

January 22, 2014From artists' monographs to beach reads, "Printed Matters" offers a monthly take by a rotating group of contributors on visual art through the printed word.

Editors: Ian Berry and Michael Duncan

Members of female Catholic religious orders (nuns) have a tendency to fall into one of two camps in contemporary popular imagination: the severe disciplinarian or the renegade. The former perception arises in part from the strictness that once accompanied all aspects of parochial education, from penmanship to punishment. (Say the name “Sister Mary DeNunzio” to selected alumni from a certain Catholic high school in New Jersey and the likely response will be an involuntary shudder.)1 The latter characterization emerged alongside the sweeping reforms of the Second Vatican Counsel in the 1960s and applies to those who commit themselves and their work to realizing social justice in the world. Think of Sister Megan Rice, a leading advocate for nuclear disarmament, or the Nuns on the Bus, whose cross-country campaigns have condemned various government policies.2

Into this latter category falls the artist Corita Kent. Although she left her religious community, the Immaculate Heart of Mary Sisters (IHM), in 1968 after thirty-two years, her philosophies about education and activism were largely shaped by this teaching order.3 The community ran the liberal-arts Immaculate Heart College (IHC) in Los Angeles, which functioned during Kent’s tenure as a center for liberal theology and “a galvanizing force for change in the Catholic Church,” according to Michael Duncan in the exhibition catalogue, Someday Is Now: The Art of Corita Kent (2013).4 Kent taught in the art department at IHC from 1947 to 1968, becoming its chair in 1964, and, together with her mentor, Sister Magdalen (Maggie) Mary Martin, advanced a pedagogical approach that incorporated experimentation, play, folk art, and the presence of outside voices in the classroom.5

Someday Is Now, which was produced to accompany the exhibition of the same name, describes with insightful detail the two sisters’ contentious working relationship, their shared teaching philosophy, and Kent’s evolution as an educator and artist.6 Duncan’s introductory essay illuminates the radical changes that took place within the Catholic Church at the time and provides a rich context for why Kent’s influence in the classroom reverberated far beyond the confines of the school for both secular and religious audiences. It succeeds most of all in extolling the artist’s masterful assimilation of texts, advertising slogans, graphic design, and pop culture into jaunty and intricate modernist collages.

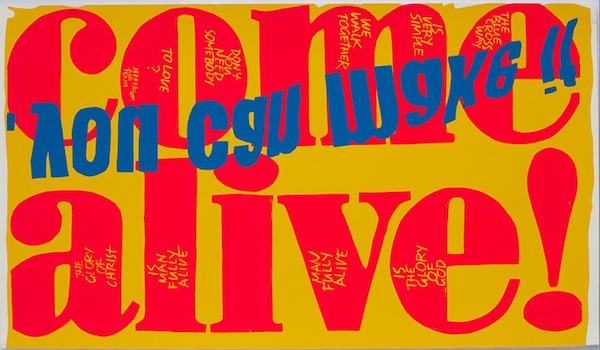

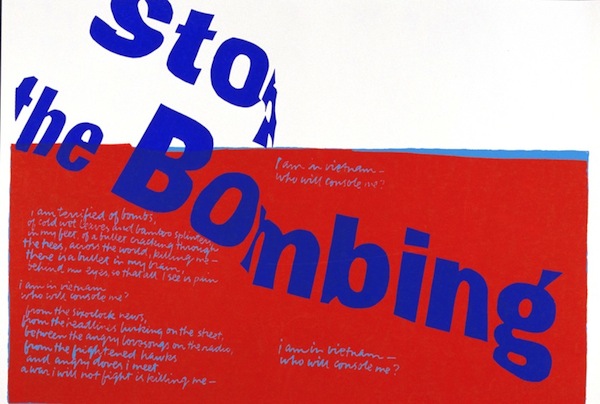

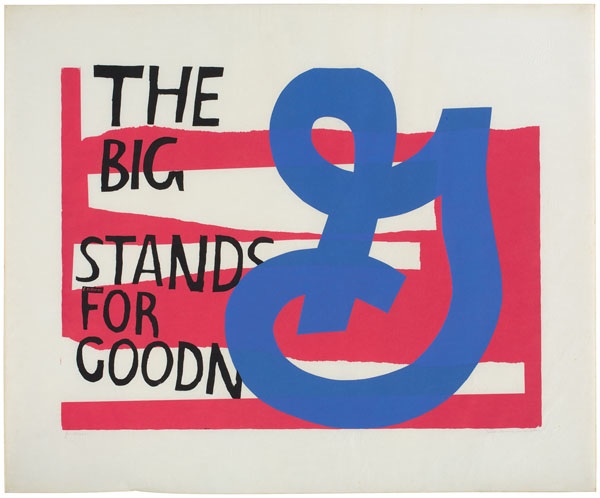

Kent’s prolific output between roughly 1960 and 1968 was the most dynamic phase of her artistic practice, which continued until her death from cancer in 1986. She embraced printmaking as an ecumenical form and produced large, unnumbered editions of serigraphs (silkscreens). It was during this period that she alighted on the process of bending, curling, and inverting letters cut from magazine ads, recombining them, photographing the results, and cutting the photographs to make the stencils for her serigraphs. Duncan describes her appropriation of advertising slogans not as critique but as “unleash[ing]…the essential humanism lurking within the advertising sales copy.”7 Kent herself described her appropriation by saying “in a way all the words we need are in the ads/they can be endlessly re-sorted and reassembled/it is a huge game/a way of confronting mystery.”8

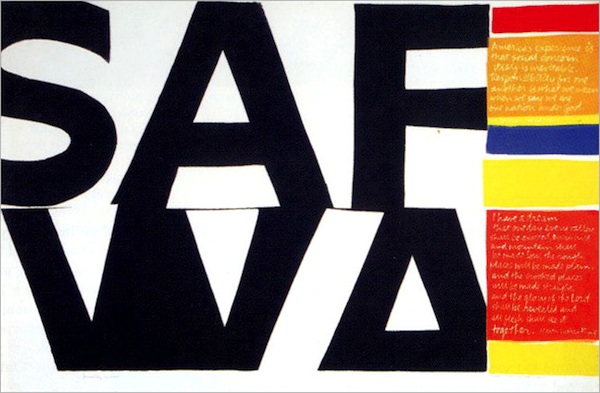

The serigraphs frequently—sometimes brilliantly—layer these branding elements with Kent’s own prose poems, or quotes from poets, songwriters, and activists as disparate as Simone Weil, e.e. cummings, Leonard Cohen, Joan Baez, and Jefferson Airplane. Rendered in her small, tight handwriting, they are murmuring affirmations of faith juxtaposed with everyday encounters writ large. For example, in the serigraph Someday Is Now (1964), the fragmented block letters of the Safeway supermarket logo nearly fills the page; squeezed in beside it are stacked bars of blue, red, orange, and lime green. Written in white on the largest two bars are passages from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.9 The simple composition unexpectedly and powerfully turns the large, black letters from a grocery-store chain into a herald of safe passage for those who would seek justice.

Corita Kent. someday is now, 1964; serigraph; 24 x 35.88 in. Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Los Angeles.

Corita Kent. someday is now, 1964; serigraph; 24 x 35.88 in. Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Los Angeles.

However, for all the emphasis placed on the visual power of Kent’s prints and her influence as an educator, the catalogue allocates insufficient space to describing the intersection between her art and activism. One has to delve into the oral history scattered throughout the book to uncover the particulars of how her work fueled progressive or even radical gestures for peace. While Duncan provides the construction of and reactions to a controversial installation commissioned for the windows of IBM’s headquarters as an example, no images of the installation are included, and it falls away as incidental.10 I would have greatly preferred a second essay that elaborated on Kent’s social agenda rather than the one included, which purportedly outlines Kent’s history as a printmaker, but in actuality provides a more general overview of the medium.

Her activism serves instead to illustrate the motivation behind her eventual relinquishment of her vows under increasing pressure from the conservative Los Angeles archdiocese. One senses a certain hedging on the part of the editors in placing an active nun, even a liberal one, too squarely in contemporary artistic practice—it would seem that a decommissioned one has more credibility in the art world. Commentary from artists such as Julie Ault, Andrea Bowers, Jim Hodges, Mike Kelley, and Pae White, among others, does much to argue for Kent’s influence on various trajectories of contemporary art production, especially those that investigate the malleability of language, appropriate popular and commercial imagery, and foment activism. Surprisingly, though, the catalogue gives scant descriptions of her close friendships with visionaries such as Buckminster Fuller, Charles and Ray Eames, John Cage, and Alfred Hitchcock. These gaps, combined with the contradictory anecdotes and testimonies that the oral history provide, give readers insight into the day-to-day sensibilities of the woman but do not add up to a complete picture of the artist. The portrait of Kent feels assembled rather than carved.

The catalogue’s design underscores this; Someday Is Now seemingly intends for readers to meander through it. One hopscotches from article to image to index and back again in search of information, especially if one is curious enough to decipher the handwritten passages. There are useful annotations in the essays on pages that contain prints, but no inverse cross-references by which one can readily locate the history of any given work when looking at the images.

For a book that celebrates the formal, inventive potential of text, certain elements either overreach or are so unobtrusive they cease to be useful. For example, titles of works and quotes by the artists suffer from a “belt and suspenders” treatment, rendered as both bold and in an alternative typeface. Alternatively, the aforementioned annotations appear in such a small, faint, fuchsia font that they are easy to overlook. But the most egregious flaw is the placement of the captions, which are tucked into the binding so that one has to crack the spine to read them, a gesture that is both careless and frustrating.

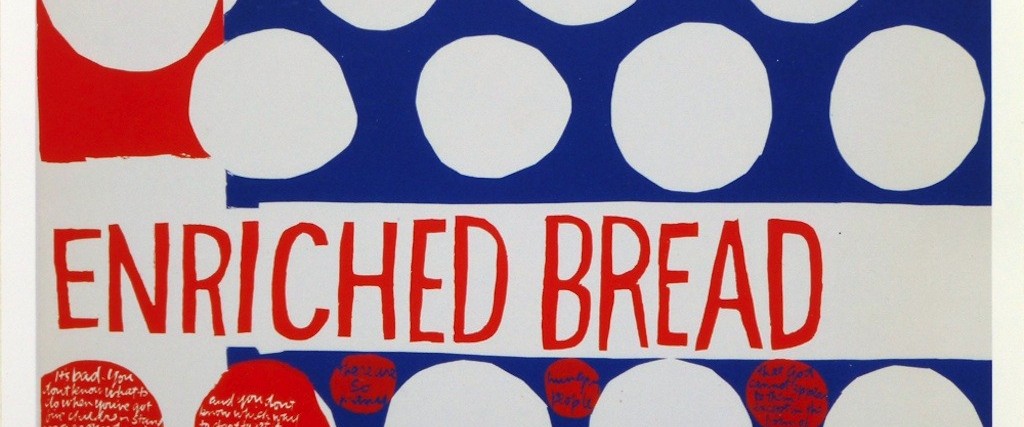

The shortcomings in design and layout, however, do not diminish the book’s capacity to serve as a resource for Kent’s work, which in itself makes the strongest case for her ongoing relevance. Lingering over the plates, one is absorbed in the joyousness of life. Kent’s compositions possess a giddy sensibility that aspires equally to the potential for change and the hard work that accompanies it. Bright primary colors pour forth from the pages; spirituality is not a transcendent abstraction but a radiant clash of text and shape. The vibrant dance of calligraphic forms humbles readers with the simplicity of the messages it delivers. For example, in That They May Have Life (1964), Wonder Bread is a vehicle that remind us, “There are so many/hungry people/that God cannot appear to them except in the form of/bread.”11 The words “Enriched Bread” hover above this assertion, encapsulating the play between wonder, grace, nourishment, and brand familiarity. These were the tenets of both Kent’s faith and her art, and the prints in Someday Is Now celebrate the capacity of one to feed the other.

Corita Kent. that they may have life, 1964; serigraph; 23 x 35.38 in. Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Los Angeles.

Corita Kent. that they may have life, 1964; serigraph; 23 x 35.38 in. Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Los Angeles.