5.3 / On Collecting

Collecting and Discovering Ming-Ju Sun: Paper-doll Cues to a Family History

December 10, 2014I longed to write this column as a personal story. I drafted a few descriptive sentences about my childhood with the paper-doll books of Ming-Ju Sun, but I became dissatisfied. Though I have accumulated her books for years, it is only recently that the character of owning them became collecting. To me, collecting is a particular gesture, one that has endless meanings. My gesture of collecting, however, is marked by a new consciousness of my relationship to a symbolic material. The books are materials of my cultural heritage—a portal to history and the artist herself.

Sun is a Chinese visual artist who has lived in the United States since the 1940s. In her undergraduate years, she studied fine art, taking classes on the history of costume and textiles as well as Chinese and Japanese history. In the early 1970s, while earning her fine-art graduate degree from the University of Maryland, she worked as a fashion illustrator for the Garfinckel’s department store.1 During that time, stores still sent hand-drawn illustrations, not photographs, to newspapers for their advertisements.

Sun’s commercial fashion work is held in the archives of the National Museum of American History, part of the Smithsonian Institution. Since the 1980s, she has hand-illustrated paper-doll, sticker, and coloring books for Dover Publishing. She also shows her fine-art canvases of colorful, thread-stitched patterns on rice in galleries in Washington, DC, where she lives.

Yet beyond all of Sun’s facts and accomplishments are the collector’s guiding questions: Why do I collect the work, and how does it speak to me?

Ming-Ju Sun is my grandmother; our connection by blood and spirit is ineffable.

Ming-Ju Sun is my grandmother; our connection by blood and spirit is ineffable. Since I was eight years old, she has mailed packages of letters and books of paper dolls to me. In the time between each package, I live with and look at the books; I turn the pages slowly. The lush colors and patterns of Chinese costumes invite me to witness their stories.

And while the boxes archived in the Smithsonian prompt certain social and cultural considerations, it is most important for me to consider the work and story of the Ming Ju-Sun who I know: to articulate the collection that brings me closer to a history often unknown by my generation.

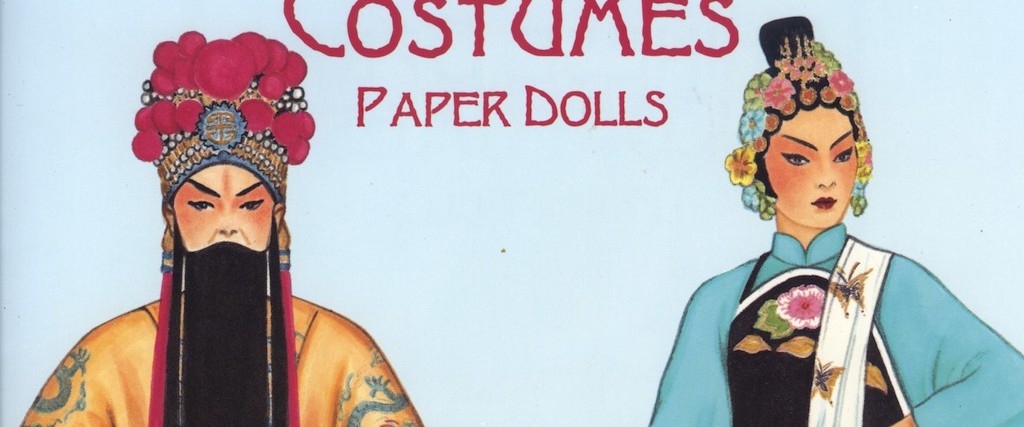

Each time I look at a book like Chinese Opera Costumes (1998), it becomes clearer how every page is a complete work of art. The hand-drawn and -painted opera character, “Good Official, Plate 10,” wears an ornate headdress with ruby-red buds in yellow embroidery. From its origins during the Song dynasty (960–1279) to the modern Peking opera (developed for a broader, Western audience), Chinese opera has always maintained a distinct style and structure. Costumes carry the weight of meaning for character and context. The official’s red-and-yellow headdress signifies the Chinese flag and associates him with state power. The red tassels mimic his long beard, suggesting the duration of his official position. His expression is balanced, allowing a feeling of trust for the auspicious power and strength symbolized by the Chinese dragons on the yellow silk robe. In her illustrations, Ming-Ju Sun recreates and represents the structure of the theater, turning the act of looking at the flat pages into vicariously viewing the opera.

The symbols of dragons and a long beard again appear in “Prime Minister, Plate 12,” but their meaning is different. The minister’s face is painted black and white; the dashes beside his eyes mimic the shape of his two-tiered black headdress. His outward expression is unsympathetic. Red and gold on the robe again signify strength and power. But Sun does not mention his virtue in the title: he is not the “Good Prime Minister.” His arms are crossed and his hands are hidden beneath long sleeves. He holds two scepters, one with a flag. All these subtle details indicate his character: the viewer should be wary of his power within a larger plot.

In traditional Chinese opera, there is little scenery, and so costumes, movements, and gestures are essential cues for context and character. The last time I visited Ming-Ju Sun, in 2008, I was struck by how a certain fling of her hand conveyed so much about her sentiment, her life and roots. I also remember how much she believed in the way clothes spoke. In her little apartment, all the closets were filled with clothes. But the pieces in her collection were never frivolous; they were eclectic and versatile, pressed and tailored. She still does all the tailoring by hand, as with her meticulous artwork. Her hand is not separate from her tastes, her experiences, and her memories.

My grandmother is private, keen to detail, and very much her own person. When I asked her in a letter about her choice to be an artist, she wrote, “By the age of thirteen, I knew I wanted to do art when I grew up.” On her relationship to drawing paper-doll books, she revealed that she had been interested in clothes design since age seven. She first got hold of blank paper while on a boat, coming to the United States. “In China during the war, such things were not available,” she wrote. “The only paper children had were tablets of lined paper for school work.”

Each page was her ode to the significance of one sheet of open, white paper.

So in her encounter with blank paper, at seven years old, Sun made her first mark as an artist. She drew a small collection of clothes that she wanted to wear after arriving in the United States. Knowing this, I felt the paper-doll pages weighted in a new way: each page was her ode to the significance of one sheet of open, white paper.

She has written to me that she remembered seeing Chinese opera as a child. It left a strong impression on her: the costumes, the dance gestures, and the music were “so different that it was unforgettable.” Now when I look at Chinese Opera Costumes, I wonder which character she identified with most as young girl: the “Female Warrior, Plate 4,” or “Older Lady in a Comic Role, Plate 3,” or “Dancer with Fan, Plate 6,” or “Elaborate Headdress Dancer with Fan, Plate 8”? Did she ever want to be the “Good Official” and not a dancer? Do her illustrations of characters embody memories of absence or longing? She does not give many direct answers to my more poignant questions. Perhaps, even among family, some aspects of history must remain mysteries, and we only have our speculations. In collecting Ming-Ju Sun’s books, I can turn to them for access, and allow her space.

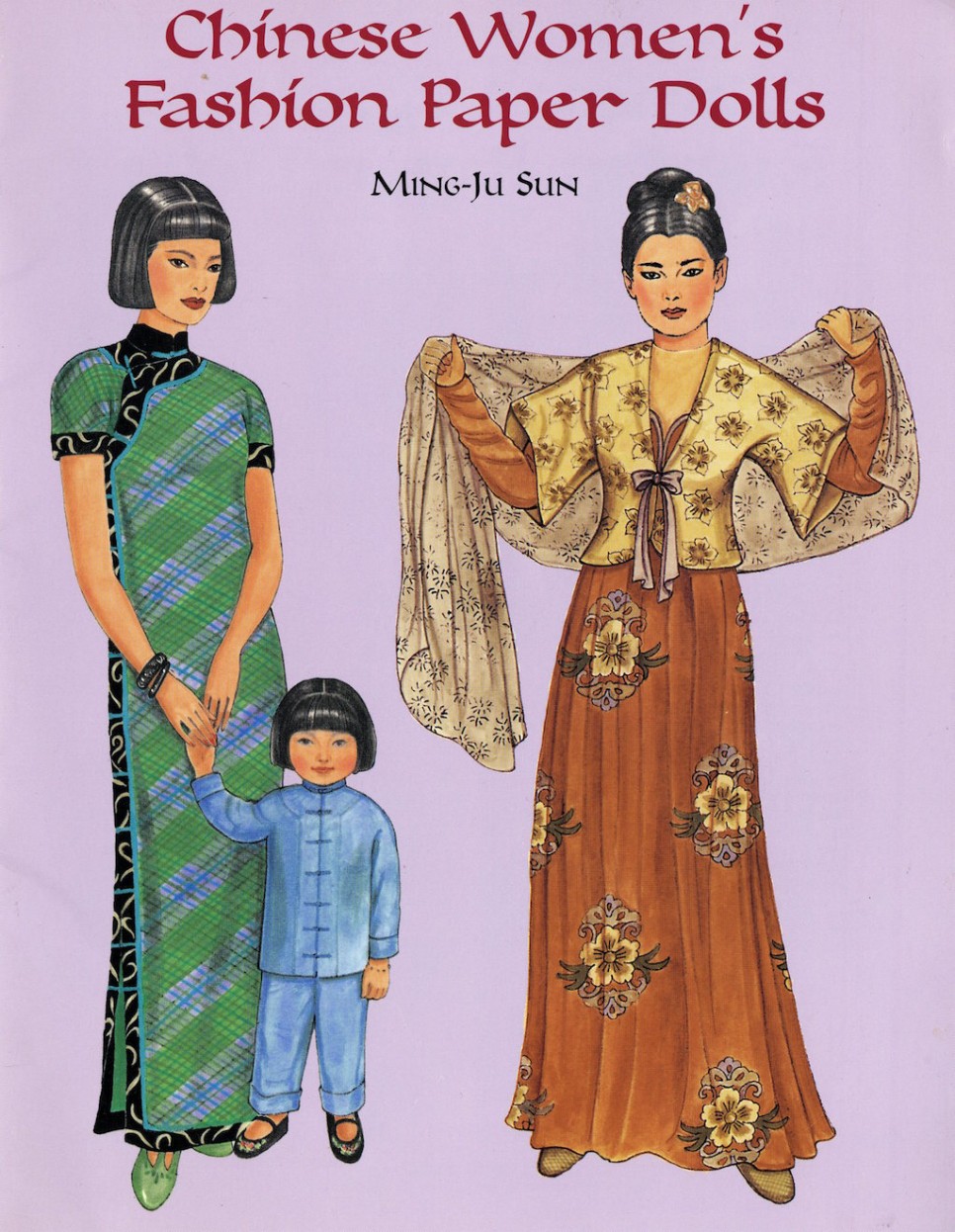

On the cover of Chinese Women’s Fashion Paper Dolls (1999) are two women and a child. Looking at this image the other day, I realized for the first time that the child was my mother, and the woman holding her hand was my grandmother. The other woman was my aunt, Diana, Ming-Ju Sun’s sister. Before my eyes were the generations of women preceding me, together as Chinese, in a way I hadn’t seen before.

A part of me desires to know Ming-Ju Sun’s history and to relate it to myself. As a writer living on the opposite side of the country from my artist grandmother, collecting the books binds our stories across generations and physical distance. Living with these books, talking to her about them, writing about them—these actions bring us closer and further the act of looking. Though we have had different experiences and have chosen different paths of expression, my grandmother has passed on to me an aesthetic appreciation: the possibilities of the blank, open page.