Shotgun Review

Một Cõi Đi Về

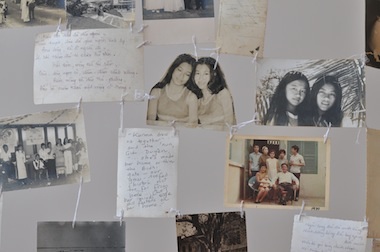

June 13, 2013One of the powers of the photographic image is its capacity to bring memories to people’s minds— either individual or shared recollections. Dinh Q. Lê’s installation presented at SF Camerawork, Một Cõi Đi Về, gathers approximately fifteen hundred photographs woven together, creating a gigantic, 14-by-22.5-foot patchwork wall of images hung from the ceiling. The last four or five rows at the bottom lie on the wooden floor, like photographs that one scatters while looking for a specific one.

Lê, a renowned Vietnamese American artist (born in Ha-Tien, Vietnam, in 1968), immigrated to Los Angeles with his family in 1979, after having endured the American conflict in Vietnam. As the artist says, “My family left Vietnam, and everything, including our photographs, was left behind.”1 Lê traveled several times back to Vietnam, visiting shops in the hope of finding his family’s photographs. He did not find any but instead collected hundreds of others’ photographs. His personal project became the art piece Một Cõi Đi Về, which the artist translates to “spending one’s life trying to find one’s way home,” a description of his personal and artistic practice.

The form of Lê’s piece implies an engagement with the audience, whose gazes hardly leave the images, as they walk around, crane their heads, and study what they see. Most of the photographs are vernacular black-and-white images of people, faces, intimate moments, or public spaces. Contrary to the journalistic imagery of the war, showing death and violence, these photographs capture different moments, some happy and others more ambiguous. Evoking a statement by Roland Barthes, the photographs of Một Cõi Đi Về go beyond the fixed memories that they show: they arouse imaginative fantasies about their subjects2.

Dinh Q. Lê. Một Cõi Đi Về, 2013; installation view, SF Camerawork. Courtesy of the Artist and SF Camerawork.

Is the groom’s face worried because he knew he would have to soon leave his new wife to fight? Are the two women close sisters or forbidden lovers? Did the young woman accept to have her portrait taken in order to get fame? Is the family-reunion photograph showing the last gathering before the sons go to war?

These captured moments acquire another layer of meaning through the Vietnamese, Chinese, or French inscriptions written by the photographs’ previous owners. They reveal a personal message of a soldier away from home, they narrate a political confrontation, or they simply mention a name and a date. Other inscriptions are by the artist himself, passages from Nguyễn Du’s The Tale of Kiều in its English translation, weaving among the personal stories a wider narrative of the diaspora3. Một Cõi Đi Về is a massive piece that allows an intimate relationship between the viewers and the images. As Lê tried to find his way home through the act of searching, viewers of his work shape their memories through the act of looking.

Một Cõi Đi Về is on view at SF Camerawork, in San Francisco, through June 22, 2013.

Pierre-François Galpin is an independent curator based in San Francisco, whose interests intersect between photography, urban studies, and media art. He is currently pursuing a Masters degree in curatorial practice at the California College of the Art.

________

Notes:

1. From the video interview “SF Camerawork presents Dinh Q. Lê, http://vimeo.com/66286793

2. “Not only is the Photograph never, in essence, a memory […], but it actually blocks memory, quickly becomes a counter-memory.” Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), p.91.

3. The Tale of Kiều (1820) is recognized as one of the most significant work in Vietnamese literature. In 3,254 verses, the epic poem narrates the life of Thúy Kiều, a young women who sacrificed herself to save her family. To Lê, many Vietnamese diaspora and migrants identify with the story of Kiều.