Shotgun Review

Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris

June 28, 2011I paint the way some people write their autobiography…. I have less and less time and yet I have more and more to say, and what I have to say is, increasingly, something about the movement of my thought.

—Pablo Picasso

This collection of “Picasso’s Picassos” comprises 150 of the thousands of pieces amassed by the artist and bequeathed by his heirs to the French government to allay its vampiric inheritance tax. Arranged chronologically, the abridged but representative array of Picasso’s career reflects his belief that painting is “just another way of keeping a diary"; the works become a multifarious self-portrait spanning seventy years. The exhibit begins with what one would swear is a Van Gogh, not merely for its effulgent colors, rough, thick brushstrokes, and the almost material quality of the light beams emanating from the candle, but also for its morbid preoccupation. La Mort De Casagemas (1901) depicts Picasso’s friend and poet, dead from suicide over a failed love affair. Picasso was twenty years old and newly enthralled by the avant-garde movement thriving in his adopted city of Paris; he quickly mastered its various innovations before launching into his Blue Period.

Skipping ahead sixty-nine years, the final work before the exit is the self-portrait The Matador (1970). After a lifetime of depicting himself as a bull, a symbol of brute power and virility, the eighty-nine-year-old painter finally surrenders what has become, in his age and failing health, a delusive persona and refashions himself as the torero. However, as if unable to portray himself without some declaration of his potency, he does include two commonplace phallic symbols, the sword and cigar (off which rise womanly curls of smoke). The brushwork is crude and urgent; the colors, simple. Evident in this piece, as in so much of his work of this final period, is the rush to create while there was still time, the compulsion to further redefine himself and to proclaim the survival of what approaching death hadn’t yet taken away. It reminds one of the dying Boris Godunov’s final cry in Mussorgsky’s eponymous opera: “I am still the Tsar!”

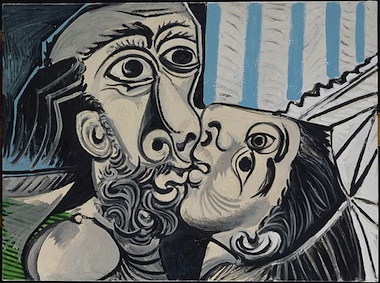

Le Baiser, 1969; oil on canvas; 38.25 × 51.25 in. Courtesy of the de Young Museum, San Francisco.

Bookended between these is an array of possibly the greatest diversity of styles ever innovated and mastered by a single artist. However, it is difficult to surmount the often unflattering portrait of the man the collection creates: the embarrassing insistence of his sexual appetites, his penchant for portraying wives and mistresses according to his own capricious loyalties, and the disturbing conflation of sexuality and violence. I admit that here I’m bringing outside knowledge to bear; 1933’s drypoints Coupling I and The Embrace are almost identical, not only to each other, but to The Rape, which is currently on display across town at SFMOMA in The Steins Collect; but perhaps the artist’s vision of the consensual and the forced as indistinct is only disturbing to the modern sensibility. And yet what more powerful antiwar statement is there (besides the obvious one by the same artist) than 1951’s Massacre in Korea? The brutal destructiveness, and also the timelessness, of war is personified by robotic soldiers with weapons from different eras, such as clubs, medieval swords, and finally, futuristic triple-barreled machine guns. Keening, pregnant women and their children represent the fragile lives left savaged in its wake. It is the sort of painting one wishes hung in the Situation Room, or the U.N., anywhere the powerful of the world convene to decide the fates of the nameless millions. It is one of the few politically charged works Picasso did, and, strangely, one of the most sensitive.

Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris is on view at the de Young Museum, in San Francisco, through October 9, 2011.

Larissa Archer is a writer and theatre worker living in San Francisco.