2.20 / Review

This Is a Picture of Me

June 28, 2011An examination of identity often starts and ends with questions: How can I measure myself, and what should I use as a yardstick? How should I mark progress, difference, change? Where is the site that the self inhabits? In attempting to answer such questions, Millee Tibbs has created This Is a Picture of Me, an exhibition of photographs that circumnavigate any number of central truths about identity but stop short of revealing its mysteries in full. In order to explore where the self is located and how it is to be understood visually, Tibbs employs multiple approaches. The exhibition is divided into three sections wherein identity is proposed as a relative property, measured against an earlier self, a landscape, or a doppelganger, respectively. Together, the investigations reveal the slippery nature of identity and the perception of identity.

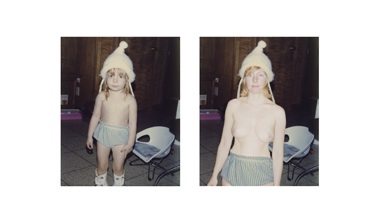

In the first section of the show, Tibbs works from childhood portraits, digitally reinserting her adult self into scenes from her youth. Each piece presents two paired Polaroid-size photographs side by side. The picture on the left shows the artist as a child, and the picture on the right shows a reproduction of the same scene that depicts the artist as an adult. In these re-creations, the adult Tibbs wears the same outfit and attempts to mimic the same face and pose captured in the original photograph. The photo pairs are titled in the manner of family-album snapshots, either by the subject and action of the photo, or simply by a date. The left-hand photo of Millee doesn’t know if it’s winter or summer 1979 (2007) shows a very young bare-chested girl wearing a pair of shorts and a fuzzy winter hat. She looks into the camera unself-consciously, arms dangling by her sides. But on the right, Tibbs’ adult face just can’t quite achieve the same good-natured blankness. Her eyes appear to confront the viewer, to acknowledge the silliness and slight discomfort of her own situation.

The photographs in this section are the most unnerving of the exhibition, not simply because they measure one self against another, younger incarnation; indeed, doing so is a common practice. In a less visual or tangible way, many people hearken back to a previous self as a measure of physical, intellectual, or emotional growth. But by placing herself physically in the scenes and clothing from her childhood, Tibbs uncomfortably squeezes herself into a mold that no longer fits. The advent of Photoshop has allowed the artist to travel back in time to the past; but these pairings demonstrate that our former states of being are not duplicable, no matter how seamlessly they are re-created. Something—an innocence, a kind of

Millee doesn’t know if it’s winter or summer 1979, 2007; pigment print; 3.25 x 4.25 in. each. Courtesy of the Artist and Blue Sky Gallery, Portland, Oregon.

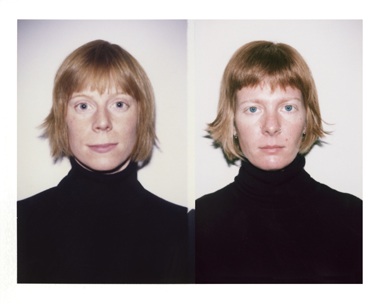

Ann/Me, 2010; pigment print, 3.25 x 4.25 in each. Courtesy of the Artist and Blue Sky Gallery, Portland, Oregon.

stainlessness—has been lost, and although the young Millee is quite comfortable with her naked chest, the adult Millee cannot erase the hint of defiance from her face when she stands before the camera exposed, because she knows.

The next section, a group of seven medium-scale pigment prints, questions the truth value of photography as it relates to identity, as well as the reliability of the artist-narrator. Each is a photograph of a landscape captioned underneath with the title of the piece, which claims the presence of the unseen artist. Self-portrait behind a Rock (2008), for instance, offers a view of a large rock, with no human subject in sight. The captions, delivered in a humorous deadpan, advance the notion that the artist is hidden behind some feature of the landscape. All of the photographs in this series are solid compositions, but after viewing the seven prints, one wonders if the joke leans too hard on the “gotcha” of all one-liners. On the other hand, a slight change to the captions’ wording would have connected the viewer back to the artist and more firmly to the question of identity. Where is the artist? She is behind the camera, of course, and since what we see is what she selected and framed, it is a form of self-portraiture because it reveals something about her taste and motivation.

In the final section of the exhibition, entitled Do You Look Like Me?, Tibbs uses passport-size headshots to question the link between physical appearance and personal identity. These photographs are also arranged in a pairing that invites comparison between the left and right images. The right photo is of Tibbs, while the left photo depicts various strangers who share similar facial features with the artist. Ann/Me (2010) shows two women looking head-on into the camera as though posing for official documentation. While not appearing as identical twins, the two women do seem kindred enough to be mistaken for one another at a glance. In each pairing, Tibbs heightens the visual similarity between herself and the other person by mimicking hairstyles and matching turtlenecks. In these photos, Tibbs measures her own identity against the stranger’s, carving out difference in the face of concurrence. Further, the size and simplicity of the photographs reinforce the feeling of sheer documentation, wherein the images exist as an indexical reference of what makes Tibbs uniquely herself even as she resembles someone else. When viewed individually, the pairings show the coincidence of features between Tibbs and the other subjects; but when taken as a group, the images reinforce the artist’s uniqueness. More than any other section of the exhibition, Do You Look Like Me? exposes the relative nature of identity and the difficulty in locating a permanent and fixed self.