7.2 / Art, Science, and Wonder

A Conversation with Ionat Zurr

October 29, 2015SymbioticA is an Artist In Residency and academic program that is located within a school of Anatomy, Physiology and Human Biology at the University of Western Australia in Perth. It was created by Ionat Zurr and her partner Oron Catts in 2000, and offers artists the opportunity to work with the most recent tools and practices available to life sciences and medical researchers. This includes advanced diagnostic machines, stem cell cultivation and all the other tools available through genetic (biological) engineering in its various forms. In 2007 I went to SymbioticA with the idea of making a video about an organism called a slime-mold. More than the access to tools, the experience placed me in a community of people who continually discussed bioethics in earnest. The experience of being there for three months changed my artwork. And, more importantly, changed my belief of what the arts can accomplish.

________

Philip Ross: When I first came to SymbioticA I was a little intimidated because I was doing things like growing compost and you guys were growing human body parts. There was a whole other level of involvement with technology. I thought you were going to be way too cool and dangerous for someone like me. But then I discovered the SymbioticA way of bringing people into the fold, including them in everything, meeting all the scientists and people there in very intimate ways through continued conversations—bringing people into a familiarity not only with the sciences but with the people and the institutions involved. This was very different from any type of residency I had ever experienced before.

Ionat Zurr: First of all, thank you for letting us know that we are uncool. SymbioticA is very much about art and life, rather than art and science. The culture is just the way we are. Because we are a laboratory in a school of Human Anatomy, we do have access to more kinds of technologies, which is an advantage because we can actually enable people who don’t have access to these kinds of things. It’s about being reflective toward what you’re doing while you’re doing it. We dreamed that this would be a place where artists and people from other disciplines could work with these technologies and could meditate about what can be done with them, considering how this affects the environment, society, and themselves in particular. This kind of approach gives the residency more of a family feel because there are many discussions. There’s no prioritizing of which technology we should work with—if it’s more complex or better—or the belief in any particular direction that these technologies can create for change. We are immigrants from a non-scientific background ourselves, so for us to be welcoming to other cultures has been something that we live and thrive on. We try and apply this to others. I very much like the outsider perspective when you’re coming into a new culture, especially if it is welcoming and opening the doors to you—it’s a great experience. I’m not saying it’s all lovey-dovey! There are also a lot of arguments, which I believe are more intellectual than personal. Once we work with life we have to share it in many respects. What are the conflicts? Why? Who’s going to benefit from it and who’s not?

PR: Yes, SymbioticA is almost like putting artists through a post-doc training, learning how to use laboratory tools and the safety protocols but also discussing ideas with other scientists so that they can understand what you’re doing and ask questions. During my residency I worked in collaboration with the manager of the university’s microscopy lab, Guy Ben-Ari. Afterward I didn’t have a clear idea of an outcome, and I think it took me another five years to create something specific from the experience. There are a lot of residencies and programs where there is this idea that you’re going to produce a piece of artwork that will demonstrate what took place, and I greatly value that there was no pressure.

IZ: For us, that is very important—it’s about research and development. You are not expected to come up with a result or an art piece that can show that your residency was successful. Not knowing where you are and what you’re doing is a sign of success because it shows that you’ve gone through a journey, that you are questioning some of the things that you came with. For many people, it’s just learning and realizing all the limitations. There is no pressure to produce, and the only thing is to engage. The only rule is that you can’t commission scientists to do the work for you. You must get your hands wet.

PR: This article is going to be read by a lot of people who are themselves working in residency programs or are considering one at their own school or institution. You have helped create a unique sort of alien, and I don’t know that you could model this as a reproducible thing.

IZ: I think it’s a sign of a general change in our society—of being able to follow risky research that does not promise certain results in the end; this has become something very difficult to do. The difference at SymbioticA is that the artists who come to the residency generate their own funding. So in a way, we’re just here to facilitate—to give you as much as we can from our expertise, resources, experience, and all that, but we don’t ask something in return besides that you do the work yourself. Now other institutions give money to artists to come over here; they trust that SymbioticA offers a meaningful residency. It could not have happened without the reputation that was built over time, but it is also something unique in this day and culture: come and explore, come and take risks, and do research for knowledge’s sake.

The laboratory space and tools that I used for cultivating the slime mold Physarum polycephalum in preparation for video microscopy. Photo: Philip Ross

The laboratory space and tools that I used for cultivating the slime mold Physarum polycephalum in preparation for video microscopy. Photo: Philip Ross

PR: I feel that the SymbioticA residency makes many visitors question their own humanity, their own feelings about life and death, and also their responsibilities. People who visit might engage in a genetic transformation or maybe in the euthanizing of an animal. I witnessed many people having these intense experiences and going through these great transformations.

IZ: They come and find we are not pushing in any direction. If you engage yourself in this technology where you are also being implicated, then the opposition of us versus other is already compromised. We’re all implicated in some way or another, but we also feel distanced because of barriers. Many people think about biological technologies when we eat certain foods, buy certain types of accessories, medications, etc. But here you are in the situation itself, and then you actually do it. And especially the genetic engineering; it’s so mundane—you mostly work with boring liquids and glassware. It’s an important realization—that a lot of it is mundane, but also a lot is abstract.

PR: When you showed Victimless Leather at Design and the Elastic Mind, the 2008 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, the museum had to kill your piece because it was growing out of control. Because of the museum’s prominence, it became a much larger issue and brought this concept to a greater public that might not have ever thought of these types of things before.

IZ: Definitely. The artwork was part of a show that was about how technology will enable new developments in the future and create these technologically mediated utopias, to a certain extent. We wanted to show our feelings, to show others our unease and the conflicts involved. We were showing a very critical piece, looking at the ironies involved in growing leather like it is a material through the use of a cell-culturing technique. We don’t think of it as a solution; we think more of it as a symptom of the problem. And that’s the beauty of things—when you start working with biological material, there are so many things that are out of control. You try and arrange everything to work the way you want, and then…

PR: …the Velociraptors escape.

IZ: Yes, exactly. This was the first time we used embryonic mouse stem cells, and we clogged the system and then got a phone call from the curator saying, “What do I do? The system is clogged. Something needs to be done.” We said, “Sorry, this is life. You will have to turn the system off.” Then she made this into a beautiful issue about turning the life-support system off, murder at the MoMA, etc. To support a technological utopia, especially a biological one, there will be so many accidents and so many mistakes and so many mutations. There are all kinds of hypocrisies in our systems to try and shift this kind of existential guilt. As artists, we try to take it up, to say, Hey, it happens, but let’s try and assess it or discuss it to see the complexities involved. Technology makes life so abstract that we forget where it came from. It can be the steak in the supermarket that is square and far removed from an animal or the people that we’re using today to operate drones—we don’t have to see the person we’re trying to kill. Victimless Leather was a piece pointing a finger at that. But when it was in the context of this show, people really desired what it promised: Yes, at last we will be able to wear leather without killing animals. The kind of accident that happened really needed to happen.

PR: This reminds me of the time you exhibited the wings you had grown out of pig tissue, and the audience killed the piece by actually touching them. Often there’s this idea that these biotechnologies will somehow escape and kill us, but it’s more the other way around—we are the most dangerous organisms in the room.

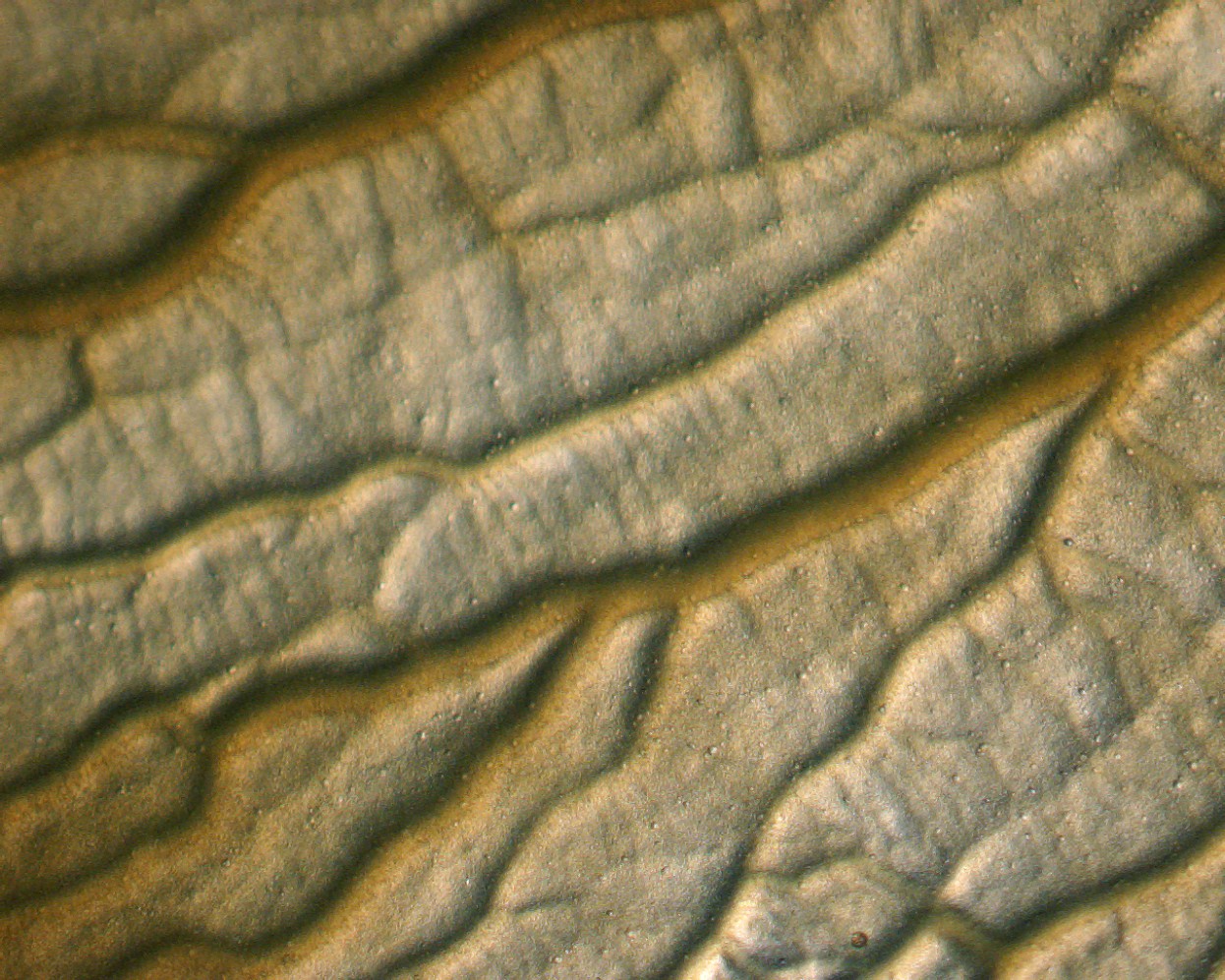

The slime mold x200. The organism moves by propogating itself by shifting the fluids within its own body and generating waves of motion. This form of locomatoin can solve complex physical logic problems, and these organisms are being studied as a type of analog biological supercomputer. Photo: Philip Ross

The slime mold x200. The organism moves by propogating itself by shifting the fluids within its own body and generating waves of motion. This form of locomatoin can solve complex physical logic problems, and these organisms are being studied as a type of analog biological supercomputer. Photo: Philip Ross

IZ: I think again that’s the problem with technology in general. There’s a lot of hype around it. When artists start to work with the technologies and talk to the scientists, they realize that all the things that they hear and observe through the media are actually hard to do: the realities are much smaller; the possibilities are much smaller. On the one hand, it creates this unrealistic kind of expectation of how we are going to solve all those problems. At the same time, we also create unrealistic fears that technology will eventually turn on us and kill us, but the reality is somewhere else.

PR: Maybe we’ll kill each other.

IZ: Yes, exactly. An idea we often talk about here is the aesthetic of disappointment. Many people find that in living art, there is a level of disappointment about what can be achieved in a project in terms of the spectacle.

PR: I know from my own experience just how difficult it is to have things stay alive inside a gallery. Galleries and museums are very inhospitable to life, which itself is an interesting realization or critical statement. For something to stay alive, it also has to be put into some type of framework, context, or care within the museum. You can’t just release these organisms—they need a container or framing device. They become a double embedded thing. How do you think an artist can actually overcome these limitations of living systems within art contexts?

IZ: We all love life, and there is also something very seductive about life manipulation, as well as the difficult acceptance in reconciling that. I think it’s especially funny because your particular artworks could be the enemy to the galleries. You’re the one they should be terrified of.

PR: This has been my well-kept secret until now, you know.

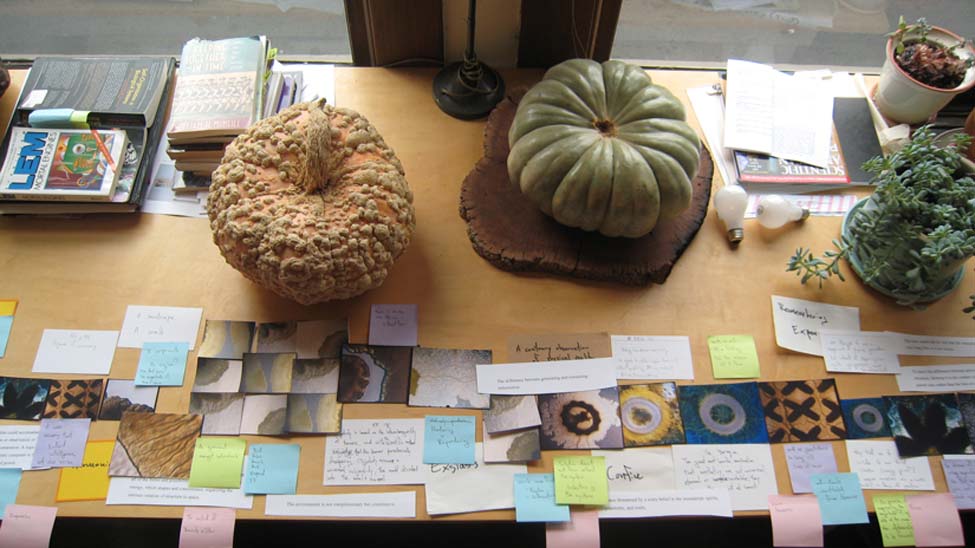

Story boarding, scripting and scoring the video images. Photo: Philip Ross

Story boarding, scripting and scoring the video images. Photo: Philip Ross

IZ: Our work involving tissue culture is useless because the moment that they are taken out of their chambers they die. We are much more dangerous than them. But a lot of framing that is done happens on many levels—one is to simply sustain and care for the life, but I think if you look through history, you see that all those kind of techno-scientific vessels and bodies reflect the aesthetics of the ideology that is involved. And we enjoy the perspective of looking at the aesthetic that is used to convey the ideas of a time—certain values, certain ethics, how life is being understood in history. How to do it successfully? I wish I had the answer. Each time we try to convey something and learn from mistakes. You can never know what other people will make out of what you’re doing, but also that’s the fun of being at SymbioticA because we have really great artists coming with their own ideas and solutions. There is always the problem of predicting how things will go, and then that becomes part of the work.

PR: When you and Oron Catts came to San Francisco in 2007 for the BioTechnique exhibition I curated at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, you exhibited these living HeLa cells that had been genetically transformed many times over the decades. We had no problem getting the permissions and equipment to actually do this, yet the most difficult thing to bring into the museum was a living bonsai tree, which we absolutely could not do. The NoArk piece you made was a Plexiglas Wunderkammer that contained these living cells, and it looked very techno-scientific. It was inside this glowing box, and within that was a beautiful tilting bio-reactor. At the museum opening I was approached by a person who works as a vivisectionist and was told how disturbing the work was to them. I was being told that we were making science look scary from a person who cuts open live chimp brains. Putting on this exhibition revealed so much about our values and fears toward biology.

IZ: I think there’s the understanding that maybe we are going in the wrong direction, one that will lead to our own demise—maybe there is a need for a completely alternative way of speaking about how to use technology and for what purpose. We have this environmental doom hanging around us with the issues of climate change and refugee crises that come from it, and I think that could change things. I don’t know how much this idea of the promise of technology will be able to survive. I think there might be some extreme backlashes. It’s going to be a very interesting period. So I think in many respects you and I believe the best.

PR: It was the best of times.

IZ: But I don’t know what will happen. We’re also having these stories of extinctions. On one hand there are so many animals becoming extinct in their environments, and then we’re trying to find technology that will put dinosaurs back into the world—like that will be the solution.

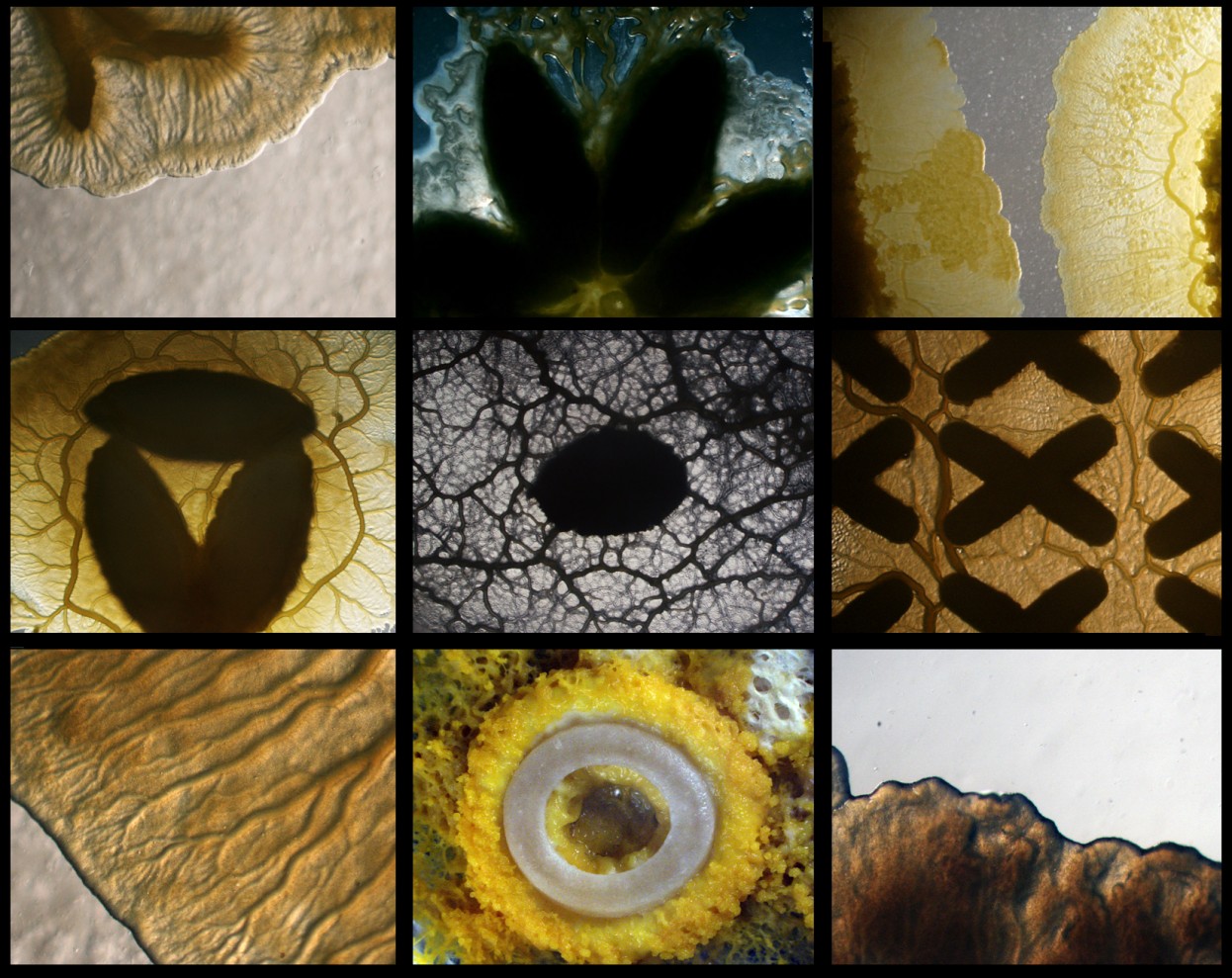

Stills from the finished video. Photo: Philip Ross

Stills from the finished video. Photo: Philip Ross

PR: They will also escape and join the Velociraptors. Do you see any promising ideas of how we might reimagine our biological circumstances?

IZ: I still remember fifteen years ago when the term epi-genetics was mentioned. It was considered a mushy subject, not scientific, and today there are epigenetics being studied in most research areas. That’s history—you have ideas that offer a simple explanation for things, and then there is the realization that things are much more complex and that we should look at things in a more holistic way. Ecology is also not the secret it used to be. With the human microbiome, you have a lot of bacteria and other organisms that you can’t capture in the lab so they don’t exist there. The only way to actually show they exist is by doing the DNA sequencing: looking at the body as an ecology rather than a software—trying to understand systems of organisms from an ecological perspective rather than just a code that can explain everything once it is deciphered. There’s no easy explanation!

PR: I’m curious about your idea of poetics, as it seems we need to find languages to describe things that aren’t as reductionist, ways of speaking about experience as living beings ourselves, not only the romantic or emotional point of view but also to speak about our being biological entities.

IZ: On poetics—here we are, emotional, unstable, beautiful, horrific, smelly, sweaty things…

PR: That’s on a good day.

IZ: There are all those methodologies to make you forget, so we try to make experiences for people that will encourage or seduce or force thinking about what it means to be in this world. Does that make sense? I don’t know. In the long term, if I think about humans on an evolutionary scale, we are here for a slight moment, and I’m not sure how much impression we leave in the long run. I see the idea of ecological collapse as a psychological way to create a behavioral change rather than a scientific one. That’s why I think many scientists are still very cautious about using the term Anthropocene to describe our situation, while humanities and cultural studies all embrace it really, really strongly. We always have to remember how bacteria changed the atmosphere when they started producing more oxygen, killing most everything else on earth.

________

Dr. Ionat Zurr is an artist, curator, researcher, and academic coordinator of SymbioticA. Together with Oron Catts, Zurr formed the Tissue Culture and Art Project. She has been an artist in residence in the School of Anatomy and Human Biology at the University of Western Australia, in Perth, since 1996 and was central to the establishment of SymbioticA in 2000. With a dissertation titled “Growing Semi-Living Art,” Zurr received her PhD from the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia. Specializing in biological and digital imaging as well as video production, she is a core researcher and academic coordinator at SymbioticA. She is considered a pioneer in the field of biological arts, and her work has been exhibited internationally.