7.2 / Art, Science, and Wonder

The Cult of the Nine Muses: Art, Science, and Wonder

October 29, 2015…here is the deepest secret nobody knows

(here is the root of the root and the bud of the bud

and the sky of the sky of a tree called life; which grows

higher than soul can hope or mind can hide)

and this is the wonder that’s keeping the stars apart…

—E.E. Cummings

Wonder—is not precisely Knowing

And not precisely Knowing not—

A beautiful but bleak condition

He has not lived who has not felt—

—Emily Dickinson

I stopped trying to deconstruct poetry back in my undergraduate days, when I realized the analysis of art left me feeling hollow, and chose instead to be on the receiving end of that same analysis (as though that feels any better). But, as I thought about this issue of Art Practical, on the occasion of the 2015 AICAD Symposium—examining the place, purpose, potential, and role of science in contemporary art and design education—I kept coming back to these lines and wondering why as I thought about . My irrational interpretation, and the one that serves our needs in this moment, is that a perpetual state of wonder, of not knowing that “beautiful but bleak condition,” is absolutely integral to our health and well-being. In other words, without it the stars would collide and all life as we know it would cease to exist.

It can be argued that every discipline carries with it the potential for great wonder, but the arts and sciences scream the value of not-knowing from the rooftops, and I believe this is the reason that they have been considered kin almost as long as civilization itself. In Ancient Greece, worshippers in the Cult of the Mousai sought inspiration from the nine daughters of Zeus (the nine Muses), who each personified a distinct discipline in the arts and sciences. Euterpe, for example, represented and distributed knowledge of music and song, while Urania was responsible for astronomy. In the great port city of Alexandria, founded in 331 BCE, muse worshipers gathered together at the Royal Library of Alexandria around a shrine known as a mousaion (what we now know as a museum).

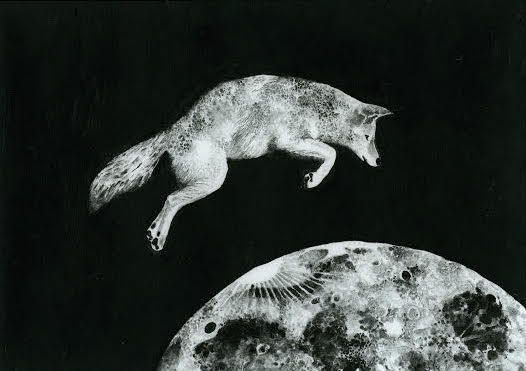

Selene Foster. Trickster visits the moon; graphite on paper; 8 x 10 in. Courtesy of the Artist

Selene Foster. Trickster visits the moon; graphite on paper; 8 x 10 in. Courtesy of the Artist

In pre-Revolutionary Paris, the regional hotbed of Enlightenment, Les Neuf Sours (The Nine Sisters), a society hoping to reignite the multidisciplinary fervor of Ancient Greece, was born and subsequently held up as a physical and conceptual structure for progressive thought. Benjamin Franklin became its second Worshipful Master, and Voltaire was initiated in 1778, a month before his death. Their position is made clear in a document presented by a Brother Amiable, which states:

The Lodge of the Nine Sisters…believes to have joined there the culture of the sciences, of letters and of the arts. This is but reclaiming their true origin. The arts have had…the unobtrusive advantage of bringing men together. It was to the sounds of the harp and voice of Orpheus that the savages of Thracia abandoned their caves. These were the fine arts that sweetened the customs of the nations; they are the preservers even to this day of the graciousness of manners. Let us labor then with zeal, with perseverance, to fill the double purpose of our institution.1

From this institution came another, the Apollonian Society, which offered laboratory space to both scientists and amateurs and taught courses in physics, chemistry, the manufacture of textiles, methods of dyeing, anatomy, and painting and drawing. The name was eventually changed to the Lycée, or French Lyceum, after the famous house of learning opened by Aristotle in Athens.

Today, too, and as you'll find in this issue, the tradition of multidisciplinary learning within the arts and sciences is alive and well. In California College of the Arts’ Science in the Studio Courses, students are given the opportunity to become scientifically literate by taking classes taught by both professional artists and “embedded” scientists. At the University of California, Santa Cruz, the research center OpenLab incorporates both studios and laboratories and encourages collaborative discourse. New York’s Stony Brook University houses the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, where scientists are taught to more effectively communicate their ideas through courses on improvisation, storytelling, and new media. Beyond establishments of higher learning, more grassroots meeting places are beginning to crop up. Noisebridge, in San Francisco, has been around since 2007 and calls itself “a hackerspace for technical-creative projects” and offers classes like Art with Software and Dream Team Neuro Hackery. Though biology hacklabs like Genspace, in New York, and BioCurious, in Sunnyvale, lean toward the science side, they actively encourage makers of all kinds to get involved.

Selene Foster. Tricksters go looking for dark matter; graphite on paper; 15 x 20 in. Courtesy of the Artist

Selene Foster. Tricksters go looking for dark matter; graphite on paper; 15 x 20 in. Courtesy of the Artist

Artists and scientists never really stopped hanging out together, but somewhere along the way we did become less acquainted and more specialized (for better or for worse). Despite the growing number of spaces where artists and scientists can learn from one another, it is unlikely that one would just stumble upon such opportunities. I also find it to be a confusing time. What do common catchphrases like “the intersection of art and science” really mean? I imagine a cross street strewn with broken beakers and splats of paint. Do I really want artists to be scientists and scientists to be artists? Is that safe? Or do I just want them to have beers together and hope the awkward conversations that ensue lead to new revelations? The answers just might lie in this issue.

Much has been discussed on the topic. Many of my own thoughts are mirrored in Johanna Kieniewicz’s post “Why Art and Science?” on her blog, At the Interface, hosted by PLOS, a well-respected science journal. So much has been said, in fact, that it is no wonder I continuously return to the musings of poets when attempting to articulate why I remain interested in the topic.

Cummings and Dickinson remind me of what got me here in the first place: it was the experience, as an artist, of learning how frogs were once used to determine the pregnancy status of humans and how cells can be herded like sheep and why my bees are acting like zombies. It was getting stuck in the goddamn mud, trying to follow a bunch of scientists out into the bay so I could watch them count eelgrass. I could go on and on, but in the end it’s all about wonder, awe, and the desire to understand what I do not.

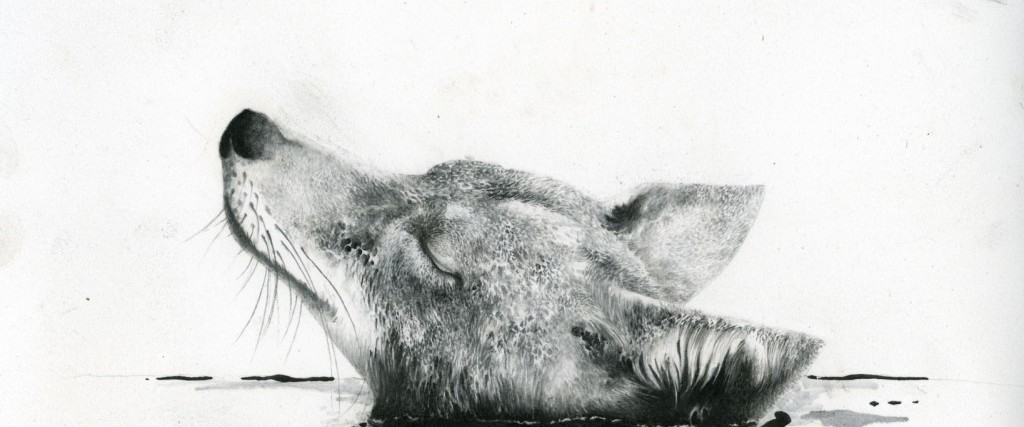

Selene Foster. Trickster goes swimming; graphite and ink on paper; 19 x 24 in. Courtesy of the Artist

Selene Foster. Trickster goes swimming; graphite and ink on paper; 19 x 24 in. Courtesy of the Artist

But who has the time? Cultivating and acting upon our experiences of wonder is a luxury few possess. And it was this reality that ultimately led to the creation of BAASICS, the nonprofit collaboration between Christopher Reiger and myself that brings artists and scientists together for live programs on a given theme. If we could capture an audience for a few hours and present them with multiple perspectives, from both the arts and the sciences, on a single topic, they would have no choice but to sit still and wonder.

I’ve come to believe that, presented with the perspectives of both artists and scientists on a given topic, the wonderment experienced by audiences increases exponentially. In other words, both fields of study have something to bring to the table, no matter what the meal. An exceptional, mainstream example of this is Green Porno, the brainchild of Isabella Rosellini. With fellow artists Jody Shapiro and Andy Byers, she was able to create what are certainly some of the most entertaining, educational short videos ever produced, a beautiful marriage of research, performance, and artistry.

Selene Foster. Trickster sees the milky way galaxy; graphite on paper; 8 x 10 in. Courtesy of the Artist

Selene Foster. Trickster sees the milky way galaxy; graphite on paper; 8 x 10 in. Courtesy of the Artist

I’ve also come to believe that presentations of scientific data improve their ability to inform and move audiences when given the attention of one or more artists. RadioLab, the beloved radio show that has also traveled as a live version, is no doubt responsible for transmitting more science (though, at times, rather soft science) to the NPR-listening masses than any other syndicated show, except perhaps Wild Kratts, another standout. And it is so successful in this regard because of the artful (often emotional) way the information is presented.

For every one of these successes, there are, and will be, embarrassing failures. But those are equally important as a means of moving us toward a future more like the past, when each discipline, like each muse, is related by birth. I encourage you, as you read these ten essays, to imagine a portly, balding Benjamin Franklin, wearing ruffles around his collar and a T-shirt reading “Worshipful Master,” swelling with pride at our fumbling attempts to reach back in time and reacquaint ourselves with the nine muses of Ancient Greece.