6.3 / Dimensions: Expanded Measures of Textiles

Three Figures, Three Patterns, Three Paradigms

February 26, 2015Introduction: Figura

The three figures presented in this essay are textile diagrams: patterns for lace and embroidery, notation systems for loom weaving, and sewing diagrams. Each embodies the historical and economic conditions from which it emerges. (The terms figure, pattern, and diagram often overlap and are somewhat interchangeable here; the point is that they all provide schematic presentations of a material process.) The present text is a draft, a kind of map for a future project that will study how the field of textile production began, in the proto-industrial workshops and mills of the sixteenth century, to codify textile practices and to render them repeatable.

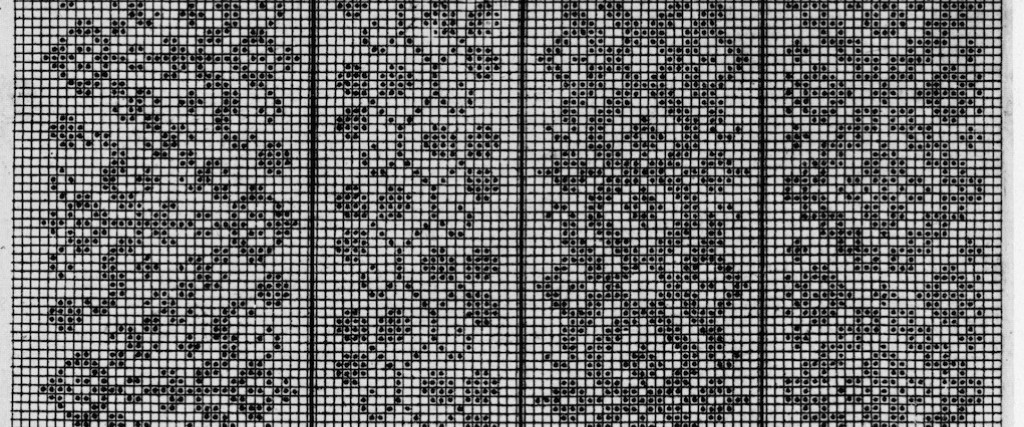

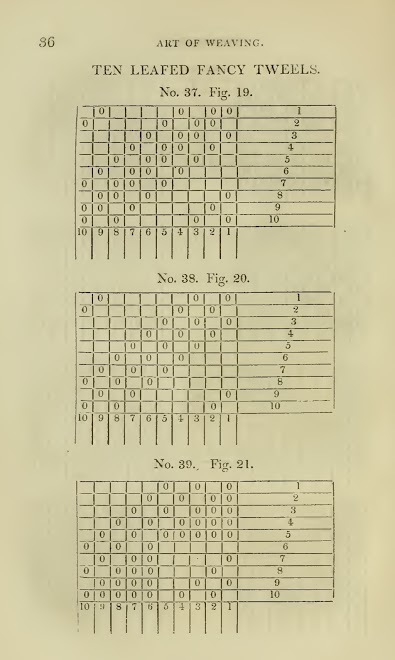

Consider an example: a page of weave drafts for twill patterns, from the Treatise on the Art of Weaving, published in Scotland in 1827 by a certain John Murphy. Identified as patterns, figures, and numbers (subsets), such illustrations ostensibly managed the activities of a population of divided textile-factory workers: those who tied up the loom and those who shuttled the weft. These images were part of a system that abstracted the conditions of labor by making it more efficient.

But we might also understand these images as devices of figuration, and more specifically, perhaps, as figures of thought.1 In Rhetorica ad Herennium, the anonymous author differentiated “Figures of Diction” (4.19-46) from “Figures of Thought” (4.47-69); while the former are identifiable in the language itself, the latter “belong in the pragmatic or situational and functional dimension of language”—that is, in the utterance (perhaps, we could say, the practice or labor of expression).2 These devices are “compelling because they map function onto form or perfectly epitomize certain patterns of thought or argument.”3

Perhaps a bit more on the philology of the word figure is needed, especially as it pertains to patterns and diagrams, and the relationship between verbal and visual iconicity.4 According to Erich Auerbach, the Latin figura initially referred quite plainly to “plastic form”; in its earliest occurrence, in Eunuchus (161 BCE), the Roman playwright Terence wrote of a young girl with an “unaccustomed form of face,” a nova figura oris (line 317).5 But over time, the term took on new meanings, expressing “something living and dynamic, incomplete and playful.” The word became “quite unplastic” as it emerged in the overlap between different senses—seeing and hearing—as figures of diction and figures of thought overtook formal shapes.6 With the Hellenization of Roman thought in the first century BCE, figura came to include a rhetorical and conceptual device: “Thus side by side with the original plastic signification and overshadowing it, there appeared a far more general concept of grammatical, rhetorical, logical, mathematical—and later even of musical and choreographic—form.”7

Thus, figures are at once plastic, technical, conceptual, and linguistic formulations.

The term figura, for instance, displaced the Greek typos, retaining its plasticity but also gaining an “inclination toward the universal, lawful, and exemplary.”8 The model and the copy, the prototype and the type converged, the temporal differentiation between the former and the latter somehow occupying a single form, the figure, which plans and represents that which has been planned simultaneously. Thus, for the Roman architect Vitruvius, the figura is a model without deception or transformation. It is a mathematically derived schematic, a diagram in the technical sense. But Auerbach notes that in “Lucretius’ doctrine of the structures that peel off things like membranes and float round in the air,” the word figura emerges side-by-side, synonymously, with simulacra, imagines, and effigies.9 Along with the plastic and the lawful, then, “‘model,’ ‘copy,’ ‘figment,’ ‘dream image’—all these meanings clung to figura”—clung like cloth, like clay.10

Thus, figures are at once plastic, technical, conceptual, and linguistic formulations. Moreover, according to Auerbach, unlike symbols, which pertain to myth or seem to have a direct connection to that which is natural, figures mediate a historical movement: a past, a present, and a future yet to come.11 Hence a figure, as in a schema or diagram, is a “plan of the future work”; it is a model and copy simultaneously, a record and a signal of a temporality—perhaps of labor—yet to come.12

So, the figures to be examined here were central to new modes of practice that turned textiles from materials into codes, from distributed practices into generally repeatable methods of production—central, that is, within the historical evolution of industrial capitalism, from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. Textura became a figura.13

1523: Patterns for Lace and Embroidery

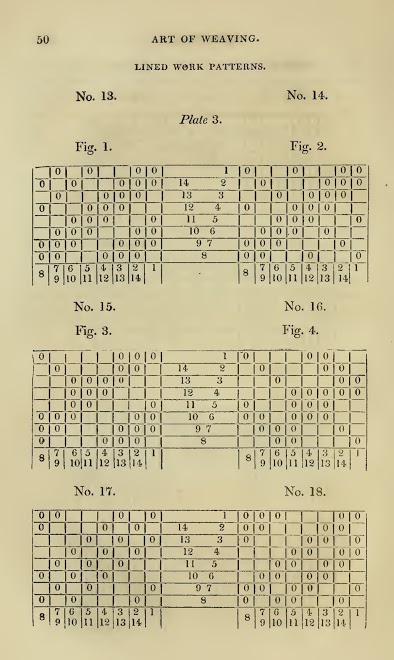

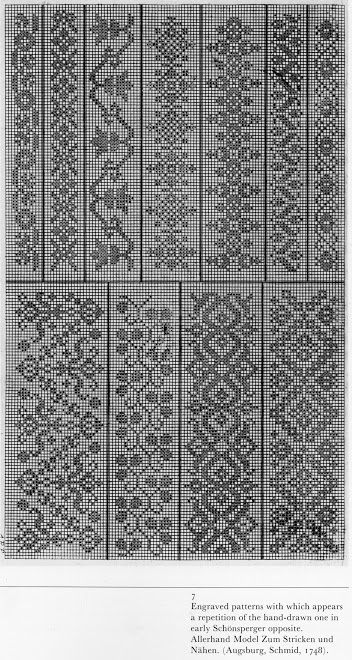

Beginning in 1523, with a volume titled Furm oder Modelbüchlein (“Form or little pattern book”) by Johann Schönsperger the Younger, print shops throughout Germany, Italy, and France began to publish patterns for lace and embroidery.14 Seen in a later book, from 1529, the crosshatched background of certain Renaissance etchings inspired Schönsperger’s major innovation, “the idea of presenting his woodcut designs in black against a background of black-and-white cross-hatching.”15 In other words, he adapted the print matrix to the fabric’s warp and weft, generating codes suited to the newly schematized methods of textile production.

Page 17 from Margaret Abegg, Apropos Patterns: For Embroidery Lace and Woven Textiles (Riggisberg, Switzerland: Abegg Stiftung, 1978).

Page 17 from Margaret Abegg, Apropos Patterns: For Embroidery Lace and Woven Textiles (Riggisberg, Switzerland: Abegg Stiftung, 1978).

The development of this diagram says a lot about the dynamic (and gendered assumptions) of this proto-industrial assemblage: of patterns, their printers, and the women who worked from them. For instance, in 1530, the Venetian printer Giovanni Andrea Vavassore initially published patterns that indicated stitches by dots, but as he was “told by several that women cannot work from freely-drawn patterns,” he later clarified the prints through the use of black squares, in order to suit a stricter economy of management and manufacture.16 Thus female workers would trace the patterns from books onto paper; then they would use these as templates for cloth, matching threads with the little blackened areas of the matrix.17 Counting stitches as they followed the template, seamstresses interlaced or drew threads in and out of nets (for filet lace) and woven cloth (for eyelet embroidery). Such a diagram figures the conditions in which the apparent femininity of lace production was systematized.

1677: Weave-draft Notation

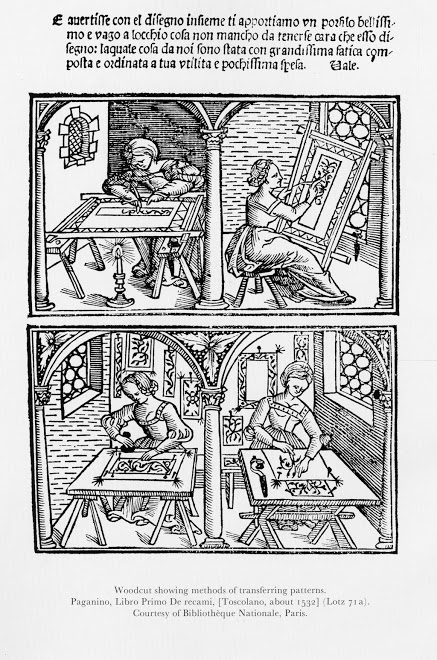

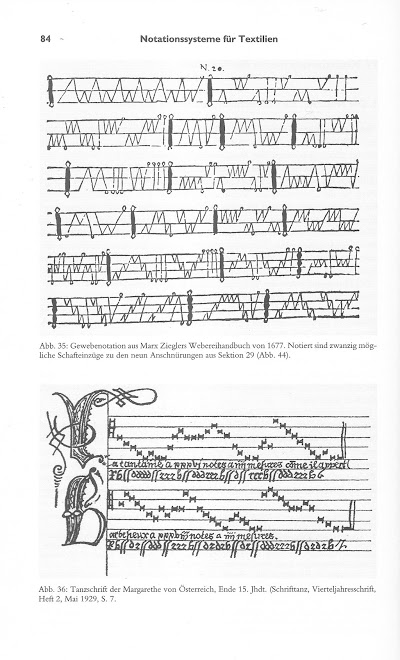

Page 84 from Birgit Schneider, Textiles Prozessieren: Eine Mediengeschichte der Lochkartenweberei (Zurich and Berlin: Diaphanes, 2007). Top: weave-notation figure by Marx Ziegler, Webereihandbuch (1677). Bottom: dance-notation figure by Margarethe von Österreich (late 15th century).

Page 84 from Birgit Schneider, Textiles Prozessieren: Eine Mediengeschichte der Lochkartenweberei (Zurich and Berlin: Diaphanes, 2007). Top: weave-notation figure by Marx Ziegler, Webereihandbuch (1677). Bottom: dance-notation figure by Margarethe von Österreich (late 15th century).

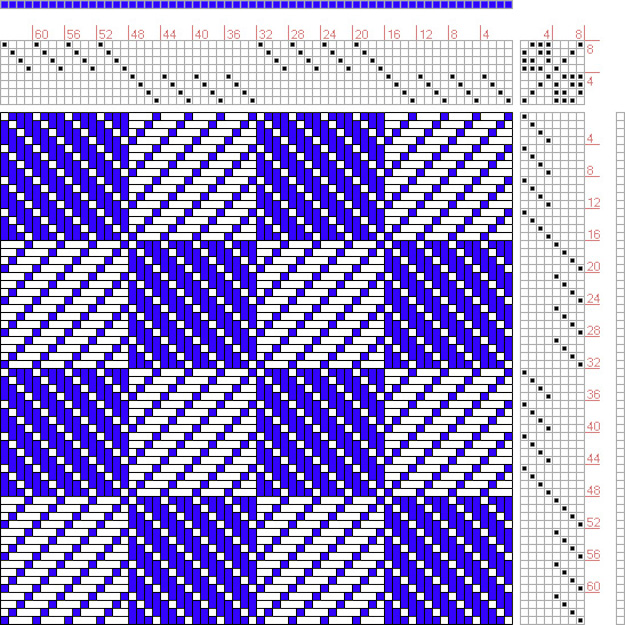

A method invented about 1677 in Germany by the master weaver Marx Ziegler recorded procedures for work at the loom. Several models emerged about this time and would be improved throughout the eighteenth century.18 Some models used grids, much like the earlier lace patterns, creating iconic representations of the woven pattern. Others were based on the mathematics of notation, an abstract system that detailed the loom’s tie-up arrangement and the sequence (or choreography) with which weavers were to shuttle the weft. These were inspired by music and dance notation.19 Eventually, by the eighteenth century, this shorthand system would prevail in the weave draft, where spaces between vertical lines denote warp threads while spaces between horizontal lines denote the weft. Filled-in squares indicate lifted threads—the forming of the shed—at this point of intersection. This new system of iconic-symbolic, or diagrammatic, notation provided a scheme for the increasingly regularized mode of textile-factory production.

Checkered cloth weave draft, from Marx Ziegler, Weber Kunst und Bild Buch (Ulm, Germany, 1677). Computer generated by Patricia Hilts. Courtesy of Handweaving.net.

Checkered cloth weave draft, from Marx Ziegler, Weber Kunst und Bild Buch (Ulm, Germany, 1677). Computer generated by Patricia Hilts. Courtesy of Handweaving.net.

By the nineteenth century, as textile mills turned into factories and as master weavers became factory managers, the weave-draft notation had so crystallized as to be taken for granted. Every mill had its own mill book, a combination of weave drafts and woven samples. But in the 1827 Treatise on the Art of Weaving mentioned earlier, the notation purports to appeal to a wider audience—to several or even many factories.

The textile industry exemplifies the mediated relationship between the worker and her labor in a capitalist economy.

Like Vitruvius, Murphy details through diagrams a mathematical usage of the Latin figura. Using a simple combination of zeros and lines, as indicators of negative and positive space, or the points where warp and weft intersect, the figures provide a plan of future work. Whereas Vitruvius envisioned De Architectura—a work dedicated to the emperor Augustus—as a grand site for theoretical, and ideological, exploration of Roman building in accordance with the concept of humanitas, Murphy’s little-known treatise on weaving was likely written for the owners and managers of factories throughout the United Kingdom. Here, diagrammatic grids, which both mimic the print matrix and the woven fabric, or bring them into collusion, ultimately coordinate the space of work. Labor and its identity within the industrial-capitalist mode of production, in 1827, is figured within these diagrams. They serve some functional end.

Hence, Karl Marx suggests that work at the loom becomes, within the capitalist mode of production, a merely formal activity, a concrete example of “abstract labour.”20 The textile industry exemplifies the mediated relationship between the worker and her labor in a capitalist economy. In other words, textiles were, for Marx, figures of the capitalist mode. They were abstracted as a medium-cum-concept—something that embodied the very condition of abstraction—where the economy of mechanization was inscribed in the weave draft’s form, its uniform grid. To put it another way: If the materiality of labor becomes abstract under capital, while the abstraction of capital becomes materialized through labor and history, then the recursive structure of the weave draft functions something like the nineteenth century’s industrial diagram. As Jakub Zdebik says of Gilles Deleuze’s take on Michel Foucault’s use of this term:

The diagram is not specific, but it is a pure abstracted function—so it can pass from one system to the next without the need to follow any similarity of form and it can intermingle with other functions, giving two incongruous systems their respective operative fields. In this way a diagram is not merely a simple model that traces similarities between things, but is also a generative device that continues working once embodied.21

1863: Sewing Diagrams

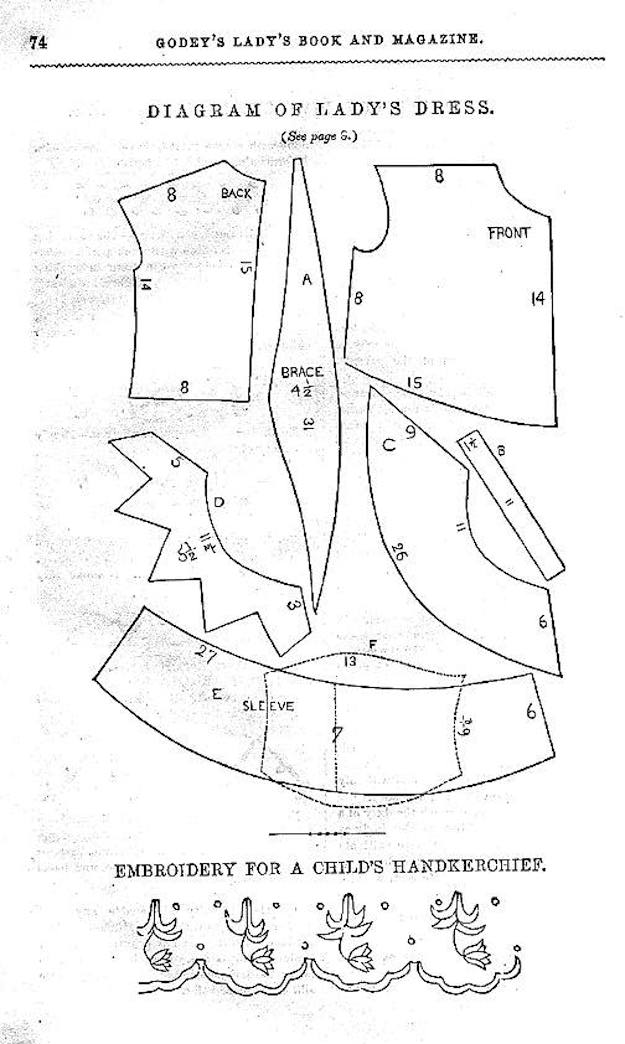

“Diagram of Lady’s Dress,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine (January 1857); reproduced by Hope Greenberg; accessed January 19, 2015, http://www.uvm.edu/~hag/godey/images/picsfashion.html.

“Diagram of Lady’s Dress,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine (January 1857); reproduced by Hope Greenberg; accessed January 19, 2015, http://www.uvm.edu/~hag/godey/images/picsfashion.html.

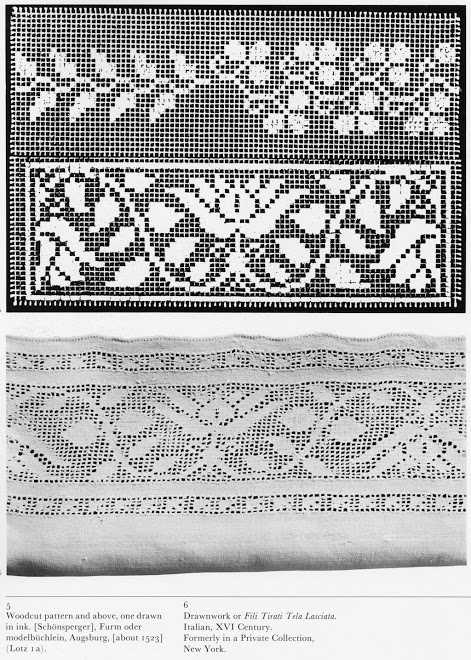

Frederik Stjernfelt, by contrast, defines the diagram in accordance with the thought of Charles Sanders Peirce: “a skeleton-like sketch of its object in terms of [rational] relations between its parts.”22 In the sewing pattern, the body is without flesh. It is a skeleton of thought, a mathematical machine. Some lines on the pattern direct the procedure of cutting while others indicate the lengthwise grain, giving the seamstress an indication of where to begin—that is, how to align the fabric’s grain, or the direction of the warp, with the pattern’s bottom and top. Such a diagram, therefore, is a device, a functional tool that helps a seamstress arrive at specified form, a particular dress. It offers a schematic ground for measuring, cutting, and connecting pieces of fabric. What is created out of this abstract figuration of the process is a material item, a piece of clothing with a certain topology.

Before sewing patterns were called patterns, before they were drafted to fit a variety of differently proportioned patrons, they were called diagrams, as seen in the magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book. Throughout the mid-to-late 1850s, this publication included inserts of dress diagrams, ostensibly offering the latest looks to its readership. But the readers, according to the economic historian Margaret Walsh, likely found these original diagrams confusing: “Pieces for several garments were superimposed on each other in intricate layers. Considerable time and patience were needed to trace the solid, broken, or combination lines onto plain paper. Once they were traced, the problem of altering the size remained, and this required the professional rather than the amateur touch.”23 Mathematical measures were needed to perfect the system of pattern drafting throughout the nineteenth century, as fashion houses such as Madame Demorest’s worked to accommodate a broader range of physical types. Walsh writes, “Though scientific principles based on the laws of proportion could offer guidance, the practical experience of tailors, dressmakers, and draftsmen was likely to produce better results as ‘average’ body measurements varied over time and place.”24 Initially, in other words, everyday women perceived the diagrams found in magazines as more figurative (that is, rhetorical) than plastic (or technical).

But in 1863, Ebenezer Butterick—motivated and assisted by his wife—determined how to grade patterns to the needed sizes. One year later, he moved his operation from Massachusetts to New York City, and the paper-pattern industry was perfected. In a warehouse in Brooklyn,

…female designers first sketched out fashionable garments. Those which met with general approval were cut in muslin and fitted carefully on human models. The resulting creations were then taken apart and given to draftsmen, who graded them into many sizes according to the Butterick method. These originals were next traced onto thick paper, and these pieces were used as the base for machine-cutting numerous “duplicates” in tissue paper. The resulting tissue sections were notched, sorted, and assembled into clearly labeled packets, illustrated by pictures of the finished garments. Cutting and sewing instructions were appended to all patterns, which were finally sorted into boxes for dispatch from the factory.25

Within a few years, the daily output of the Butterick factory reached twenty-three thousand patterns. With the marketing of paper patterns to a wide audience of working- and middle-class female patrons, fashion was democratized.

Conclusion: Paradigms

These patterns, notation systems, and diagrams figure as paradigms. They demonstrate the historical characters or multifaceted genres of capitalism.26 Like these textile diagrams, capitalism’s various instantiations—from proto- to early- to late-industrial systems—show how capital is a system of quantitative regularity and, at the same time, an eminently adaptable form.

The first figure in this essay, indeed, was subsumed by the second, with the crosshatched grid of lace patterns giving way to a system of notation: the weave draft. Meanwhile, the third figure, the aberrant sewing diagram, leaves the grid and attempts to accommodate the irregular shapes of the body; it marks a shift toward a flexible model of production. More befitting the mechanisms of consumer capital, the sewing diagram has the capacity to democratize itself, to remold itself.27 As George Kubler would say, “From time to time the whole pattern shakes and quivers, settling into new shapes and figures.”28